SHARE THE KNOWLEDGE If you like this blog, please subscribe or follow for latest update

Saturday, October 10, 2015

The Russian Revolution : The Revolution of October 1917

The

Revolution of October 1917:

As the conflict between the Provisional Government

and the Bolsheviks grew, Lenin feared the Provisional Government would set up a

dictatorship. In September, he began discussions for an uprising against the

government. Bolshevik supporters in the army, soviets and factories were

brought together.

On 16 October 1917, Lenin persuaded the Petrograd

Soviet and the Bolshevik Party to agree to a socialist seizure of power. A Military

Revolutionary Committee was appointed by the Soviet under Leon Trotskii to

organise the seizure. The date of the event was kept a secret. The uprising

began on 24 October. Sensing trouble, Prime Minister Kerenskii had left

the city to summon troops. At dawn, military men loyal to the government seized the buildings of

two Bolshevik newspapers. Pro-government troops were sent to take over

telephone and telegraph offices and protect the Winter Palace. In a

swift response, the Military Revolutionary Committee ordered its supporters to

seize government offices and arrest ministers. Late in the day, the ship Aurora shelled the Winter

Palace. Other vessels sailed down the Neva and took over various military

points. By nightfall, the city was under the committee.s control and the ministers

had surrendered. At a meeting of the All Russian Congress of Soviets in

Petrograd, the majority approved the Bolshevik action. Uprisings took place in

other cities. There was heavy fighting . especially in Moscow . but by

December, the Bolsheviks controlled the Moscow-Petrograd area.

What

Changed after October?

The Bolsheviks were totally opposed to private

property. Most industry and banks were nationalised in November 1917. This

meant that the government took over ownership and management. Land was declared

social property and peasants were allowed to seize the land of the nobility. In

cities, Bolsheviks enforced the partition of large houses according to family

requirements. They banned the use of the old titles of aristocracy. To assert

the change, new uniforms were designed for the army and officials, following a clothing

competition organised in 1918 . when the Soviet hat (budeonovka)

was chosen.

The Bolshevik Party was renamed the Russian

Communist Party (Bolshevik). In November 1917, the Bolsheviks conducted the elections

to the Constituent Assembly, but they failed to gain majority support. In

January 1918, the Assembly rejected Bolshevik measures and Lenin dismissed the

Assembly. He thought the All Russian Congress of Soviets was more democratic

than an assembly elected in uncertain conditions. In March 1918, despite

opposition by their political allies, the Bolsheviks made peace with Germany at

Brest Litovsk. In the years that followed, the Bolsheviks became the only party

to participate in the elections to the All Russian Congress of Soviets, which

became the Parliament of the country. Russia became a one-party state. Trade

unions were kept under party control. The secret police (called the Cheka

first, and later OGPU and NKVD) punished those who criticised the

Bolsheviks. Many young writers and artists rallied to the Party because it

stood for socialism and for change. After October 1917,

this led to experiments in the arts and

architecture. But many became disillusioned because of the censorship the Party

encouraged.

The

October Revolution and the Russian Countryside: Two Views

News of the revolutionary uprising of October 25,

1917, reached the village the following day and was greeted with enthusiasm; to

the peasants it meant free land and an end to the war. ...The day the news

arrived, the landowner.s manor house was looted, his stock farms were

.requisitioned. and his vast orchard was cut down and sold to the peasants for

wood; all his far buildings were torn down and left in ruins while the land was

distributed among the peasants who were prepared to live the new Soviet life..

From:

Fedor Belov, The History of a Soviet Collective Farm

A member of a landowning family wrote to a relative

about what happened at the estate:

.The .coup. happened quite painlessly, quietly and

peacefully. .The first days were unbearable.. Mikhail Mikhailovich [the estate

owner] was calm...The girls also.I must say the chairman behaves correctly and

even politely. We were left two cows and two horses. The servants tell them all

the time not to bother us. .Let them live. We vouch for their safety and

property. We want them treated as humanely as possible...

.There are rumours that several villages are trying

to evict the committees and return the estate to Mikhail Mikhailovich. I don.t

know if this will happen, or if it.s good for us. But we rejoice that there is

a conscience in our people....

From:

Serge Schmemann, Echoes of a Native Land. Two Centuries of a Russian Village

(1997).

Labels:

1905,

1917,

Bloody,

Bolshevik,

Christianity,

February,

Lenin,

october,

Petrograd,

Rasputin,

red,

Revolution,

Revolutionary,

Russian,

Soviet Union,

Vladimir

The Russian Revolution : After February

After February:

Army officials, landowners and industrialists were influential in the Provisional Government. But the liberals as well as socialists among them worked towards an elected government. Restrictions on public meetings and associations were removed. ‘Soviet’, like the Petrograd Soviet, were set up everywhere, though no common system of election was followed.

Army officials, landowners and industrialists were influential in the Provisional Government. But the liberals as well as socialists among them worked towards an elected government. Restrictions on public meetings and associations were removed. ‘Soviet’, like the Petrograd Soviet, were set up everywhere, though no common system of election was followed.

In April 1917, the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin

returned to Russia from his exile. He and the Bolsheviks had opposed the war since

1914. Now he felt it was time for soviets to take over power. He declared that

the war be brought to a close, land be transferred to the peasants, and banks

be nationalised. These three demands were Lenin’s ‘April Theses’. He

also argued that the Bolshevik Party rename itself the Communist Party to indicate its

new radical aims. Most others in the Bolshevik Party were initially surprised

by the April Theses. They thought that the time was not yet ripe for a socialist

revolution and the Provisional Government needed to be supported. But the

developments of the subsequent months changed their attitude. Through the

summer the workers’ movement spread. In industrial areas, factory committees

were formed which began questioning the way industrialists ran their factories.

Trade unions grew in number. Soldiers’ committees were formed in the army. In

June, about 500 Soviets sent representatives to an All Russian Congress of

Soviets. As the Provisional Government saw its power reduce and Bolshevik

influence grow, it decided to take stern measures against the spreading

discontent. It resisted attempts by workers to run factories and began

arresting leaders. Popular demonstrations staged by the Bolsheviks in July 1917

were sternly repressed. Many Bolshevik leaders had to go into hiding or flee. Meanwhile

in the countryside, peasants and their Socialist Revolutionary leaders pressed

for a redistribution of land. Land committees were formed to handle this.

Encouraged by the Socialist Revolutionaries, peasants seized land between July

and September 1917.

Date of the Russian Revolution

Russia followed the Julian calendar until 1 February 1918. The country then changed to the Gregorian calendar, which is followed everywhere today. The Gregorian dates are 13 days ahead of the Julian dates. So by our calendar, the ‘February Revolution’ took place on 12th March and the .October. Revolution took place on 7th November.

Vladimir

Ilyich Lenin

The

Tasks of the Proletariat in the Present Revolution

[a.k.a.

The April Theses]

Published: April 7, 1917 in Pravda No. 26. Signed: N.

Lenin. Published according to the newspaper text.

Source: Lenin’s Collected Works, Progress Publishers, 1964, Moscow, Volume 24, pp. 19-26.

Translated: IsaacsBernard

Transcription: Zodiac

Public Domain: Lenin Internet Archive (2005), marx.org (1997), marxists.org (1999). You may freely copy, distribute, display and perform this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit “Marxists Internet Archive” as your source.

Source: Lenin’s Collected Works, Progress Publishers, 1964, Moscow, Volume 24, pp. 19-26.

Translated: IsaacsBernard

Transcription: Zodiac

Public Domain: Lenin Internet Archive (2005), marx.org (1997), marxists.org (1999). You may freely copy, distribute, display and perform this work; as well as make derivative and commercial works. Please credit “Marxists Internet Archive” as your source.

This article contains Lenin’s famous April Theses

read by him at two meetings of the All-Russia Conference of Soviets of Workers’

and Soldiers’ Deputies, on April 4, 1917.

[Introduction]

Labels:

1905,

1917,

Bloody,

Bolshevik,

Christianity,

February,

Lenin,

october,

Petrograd,

Rasputin,

red,

Revolution,

Revolutionary,

Russian,

Soviet Union,

Vladimir

The Russian Revolution : The February Revolution in Petrograd

The

February Revolution in Petrograd

In the winter of 1917, conditions in the capital,

Petrograd, were grim. The layout of the city seemed to emphasise the divisions

among its people. The workers’ quarters and factories were located on the right bank of the River Neva. On the left bank were the

fashionable areas, the Winter Palace, and official buildings, including the

palace where the Duma met. In February 1917, food shortages were deeply felt in the workers. quarters. The winter was very cold .

there had been exceptional frost and heavy snow. Parliamentarians wishing to preserve

elected government, were opposed to the Tsar’s desire to dissolve the Duma.

On 22 February, a lockout took place at a factory on

the right bank. The next day, workers in fifty factories called a strike in

sympathy. In many factories, women led the way to strikes.This came to be

called the International Women’s Day. Demonstrating workers crossed from

the factory quarters to the centre of the capital - the Nevskii Prospekt. At

this stage, no political party was actively organising the movement. As the fashionable

quarters and official buildings were surrounded by workers, the government

imposed a curfew. Demonstrators dispersed by the evening, but they came back on

the 24th and 25th. The government called out the cavalry and police to keep an

eye on them.

On Sunday, 25 February, the government suspended the

Duma. Politicians spoke out against the measure. Demonstrators returned in

force to the streets of the left bank on the 26th. On the 27th, the Police

Headquarters were ransacked. The streets thronged with people raising slogans

about bread, wages, better hours and democracy. The government tried to control

the situation and called out the cavalry once again. However, the cavalry

refused to fire on the demonstrators. An officer was shot at the barracks of a

regiment and three other regiments mutinied, voting to join the striking

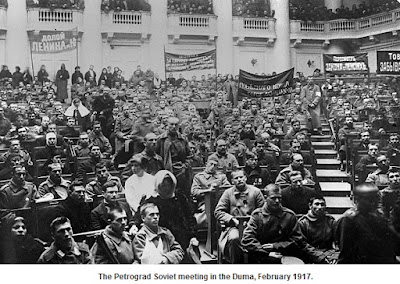

workers. By that evening, soldiers and striking workers had gathered to form a ‘soviet’

or ‘council’ in the same building as the Duma met. This was the Petrograd

Soviet. The very next day, a delegation went to see the Tsar. Military commanders

advised him to abdicate. He followed their advice and abdicated on 2 March.

Soviet leaders and Duma leaders formed a Provisional Government to run the

country. Russia.s future would be decided by a constituent assembly, elected on

the basis of universal adult suffrage. Petrograd had led the February

Revolution that brought down the monarchy in February 1917.

Labels:

1905,

1917,

Bloody,

Bolshevik,

Christianity,

February,

Lenin,

october,

Petrograd,

Rasputin,

red,

Revolution,

Revolutionary,

Russian,

Soviet Union,

Vladimir

The Russian Revolution :The First World War and the Russian Empire

The

First World War and the Russian Empire

In 1914, war broke out between two European

alliances . Germany, Austria and Turkey (the Central powers) and France,

Britain and Russia (later Italy and Romania). Each country had a global empire and

the war was fought outside Europe as well as in Europe. This was the First

World War. In Russia, the war was initially popular and people rallied around

Tsar Nicholas II. As the war continued, though, the Tsar refused to consult the

main parties in the Duma. Support wore thin. Anti-German sentiments ran high,

as can be seen in the renaming of St Petersburg -a German name -as Petrograd.

The Tsarina Alexandra.s German origins and poor advisers, especially a monk

called Rasputin, made the autocracy unpopular.

The First World War on the ‘eastern front’ differed

from that on the ‘western front’. In the west, armies fought from trenches

stretched along eastern France. In the east, armies moved a good deal and fought

battles leaving large casualties. Defeats were shocking and demoralizing.

Russia’s armies lost badly in Germany and Austria between 1914 and 1916. There

were over 7 million casualties by 1917. As they retreated, the Russian army

destroyed crops and buildings to prevent the enemy from being able to live off

the land. The destruction of crops and buildings led to over 3 million refugees

in Russia. The situation discredited the government and the Tsar. Soldiers did

not wish to fight such a war. The war also had a severe impact on industry.

Russia’s own industries were few in number and the country was cut off from

other suppliers of industrial goods by German control of the Baltic Sea.

Industrial equipment disintegrated more rapidly in Russia than elsewhere in Europe.

By 1916, railway lines began to break down. Able-bodied men were called up to

the war. As a result, there were labour shortages and small workshops producing

essentials were shut down. Large supplies of grain were sent to feed the army.

For the people in the cities, bread and flour became scarce. By the winter of

1916, riots at bread shops were common.

Labels:

1905,

1917,

Bloody,

Bolshevik,

Christianity,

February,

Lenin,

october,

Petrograd,

Rasputin,

red,

Revolution,

Revolutionary,

Russian,

Soviet Union,

Vladimir

The Russian Revolution Extars

April Theses:

The April Theses were a series of directives issued by the Bolshevik leader Vladimir Lenin upon his return to Petrograd (Saint Petersburg), Russia from his exile in Austria via Germany and Finland. The Theses were mostly aimed at fellow Bolsheviks in Russia and returning to Russia from exile. He called for soviets (workers' councils) to take power (as seen in the slogan "all power to the soviets"), denounced liberals and social democrats in the Provisional Government, called for Bolsheviks not to cooperate with the government, and called for new communist policies. The April Theses influenced the July Days and October Revolution in the next months and are identified with Leninism. The April Theses were published in the Bolshevik newspaper Pravda and read by Lenin at two meetings of the All-Russia Conference of Soviets of Workers' and Soldiers' Deputies, on 16 April 1917 (4 April according to the old Russian Calendar).

Pravda:

Pravda was the official newspaper of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and was one of the most influential papers in the country. A successor Russian political newspaper is today run by the Communist Party of the Russian Federation, however it is greatly smaller in scope and remains obscure. The newspaper began publication in 1912 in the Russian Empire and emerged as a leading newspaper of the Soviet Union after the October Revolution. The newspaper was an organ of the Central Committee of the CPSU between 1912 and 1991.

After the dissolution of the USSR, Pravda was sold off by Russian President Boris Yeltsin. As was the fate of many of the Soviet-era enterprises Pravda suffered a downturn and was sold to a Greek business family. The Communist Party of the Russian Federation acquired the newspaper in 1997 and established it as its principal mouthpiece. Pravda is still functioning from the same headquarters on Pravda Street in Moscow where it was published in the Soviet days. During its heyday Pravda was selling millions of copies per day compared to the current print run of just one hundred thousand copies.

During the Cold War, Pravda was well known in the West for its pronouncements as the official voice of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. (Similarly Izvestia was the official voice of the Soviet government.)

Pravda was closed down for a brief period on July 30, 1996. Some of Pravda 's journalists established their own English language online newspaper known as Pravda Online. Pravda is witnessing hard times and the number of its staff members and print run has been significantly reduced. During the Soviet era it was a daily newspaper but today it publishes three times a week.

Pravda still operates from the same headquarters at Pravda Street from where journalists used to prepare Pravda everyday during the Soviet era. It operates under the leadership of journalist Boris Komotsky. A function was organized by the CPRF on 5 July 2012 to celebrate the 100 years of Pravda.

Labels:

1905,

1917,

Bloody,

Bolshevik,

Christianity,

February,

Lenin,

october,

Petrograd,

Rasputin,

red,

Revolution,

Revolutionary,

Russian,

Soviet Union,

Vladimir

The Russian Revolution: 1905

Subscribe this blog by clicking "Join this Site" Button.

Go to Download Page for French, Russian Revolution

A Turbulent Time: The 1905 Revolution

Russia was an autocracy. Unlike other European rulers,

even at the beginning of the twentieth century, the Tsar was not subject to

parliament. The Revolution of 1905 was a wave of mass

political and social unrest that spread through vast areas of the Russian

Empire, some of which was directed at the government. It led to Constitutional

Reform including the establishment of the State Duma of the Russian

Empire, the multi-party system, and the Russian Constitution

of 1906.

According to the author Sidney Harcave, who

wrote The Russian Revolution

of 1905, there were four problems in Russian society at the time

that contributed to the revolution: the agrarian problem, the nationality

problem, the labour problem, and the educated class problem (http://thoughtcrackers.blogspot.in/2015/10/russian-revolution-economy-and-society.html). Taken individually, these issues may not have affected the course of

Russian history, but combined, the problems created the conditions for a

potential revolution.

At the start of the 20th century, Russian

progressives formed the Union of Zemstvo Constitutionalists

(1903) and the Union of Liberation (1904) which called for a

constitutional monarchy. Russian socialists formed two major groups: the Socialist-Revolutionary

Party, following the Russian populist tradition, and the Marxist Russian

Social Democratic Labour Party. Liberals in Russia campaigned to end this

state of affairs. Together with the Social Democrats and Socialist Revolutionaries;

they worked with peasants and workers during the revolution of 1905 to demand a

constitution. They were supported in the empire by nationalists (in Poland for

instance) and in Muslim-dominated areas by jadidists (Muslims

within the Russian empire) who wanted Islam to lead

their societies. The year 1904 was a particularly bad one for Russian workers.

Prices of essential goods rose so quickly that real wages (Reflects

the quantities of goods which the wages will actually buy) declined

by 20 %. The membership of workers’ associations rose dramatically. When four

members of the Assembly of Russian Workers, which had been formed in 1904, were

dismissed at the Putilov Iron Works, there was a call for industrial

action. Over the next few days over 110,000 workers in St Petersburg

went on strike demanding a reduction in the working day to eight hours, an

increase in wages and improvement in working conditions. In 1904, massive strike waves broke out in Odessa

in the spring, Kiev in July, and Baku in December.

This all set the stage for the strikes in St. Petersburg in December 1904 to

January 1905 seen as the first step in the 1905 revolution.

Start of the revolution:

In December 1904, a strike occurred at the Putilov

plant (a railway and artillery supplier) in St. Petersburg.

Sympathy strikes in other parts of the city raised the number of strikers to 150,000

workers in 382 factories. By 21 January [O.S. 8

January] 1905, the city had no electricity and newspaper distribution was

halted. All public areas were declared closed.

In the pre-dawn winter darkness of the morning of

Sunday, 22 January [O.S. 9 January] 1905, Controversial

Orthodox priest Georgy Gapon, who headed a police-sponsored

workers' association, led striking workers and their families began to gather

at six points in the industrial outskirts of St Petersburg to the Winter

Palace to deliver a petition to the Tsar. Holding

religious icons and singing hymns and patriotic songs (particularly

"God Save the Tsar!"), a crowd of "more than

3,000" proceeded without police interference towards the Winter

Palace, the Tsar's official residence. The crowd, whose mood was quiet, did not

know that the Tsar was not in residence. Insofar as there was firm planning,

the intention was for the various columns of marchers to converge in front of

the palace at about 2pm. Estimates of the total numbers involved range wildly

from police figures of 3,000 to organizers' claims of 50,000. Initially it was

intended that women, children and elderly workers should lead, to emphasize the

united nature of the demonstration. On reflection however, younger men moved to

the front to make up the leading ranks. The troops guarding the Winter Palace were ordered to tell the

demonstrators not to pass a certain point, according to Sergei Witte, and

at some point, troops opened fire on the demonstrators, resulting in between

200 (according to Witte) to 1000 deaths.

Half of European Russia's industrial workers went on

strike in 1905, and 93.2% in Poland. There were also strikes

in Finland and the Baltic coast. In Riga, 80

protesters were killed on 26 January [O.S 13 January] 1905, and

in Warsaw a few days later over 100 strikers were shot on the

streets. By February, there were strikes in the Caucasus, and by April, in

the Urals and beyond. In March, all higher academic institutions were

forcibly closed for the remainder of the year, adding radical students to the

striking workers. A strike by railway workers on 21 October [O.S. 8

October] 1905 quickly developed into a general strike in Saint Petersburg

and Moscow.

With the unsuccessful and bloody Russo-Japanese

War (1904–1905) there was unrest in army reserve units. In 1905, there

were naval mutinies at Sevastopol, Vladivostok,

and Kronstadt, peaking in June with the mutiny aboard the

battleship Potemkin. The

mutinies were disorganised and quickly crushed. Despite these mutinies, the

armed forces were largely apolitical and remained mostly loyal, if

dissatisfied — and were widely used by the government to control the 1905

unrest.

Nationalist groups had been angered by the Russification undertaken

since Alexander II. The Poles, Finns, and the Baltic provinces all sought

autonomy, and also freedom to use their national languages and promote their

own culture. Muslim groups were also active — the First

Congress of the Muslim Union took place in August 1905. Certain groups took

the opportunity to settle differences with each other rather than the

government. Some nationalists undertook anti-Jewish pogroms,

possibly with government aid, and in total over 3,000 Jews were killed.

The number of prisoners throughout the Russian

Empire, which had peaked at 116,376 in 1893, fell by over a third to a record

low of 75,009 in January 1905, chiefly because of several mass amnesties

granted by the Tsar after October manifesto.

On 12 January the Tsar appointed Dmitri

Feodorovich Trepov as governor in St Petersburg and dismissed the Minister

of the Interior, Pyotr Sviatopolk-Mirskii, on 18 February [O.S. 5

February] 1905. He appointed a government commission "to enquire

without delay into the causes of discontent among the workers in the city of St

Petersburg and its suburbs" in view of the strike movement. It was also meant

to have included workers’ delegates elected according to a two-stage system.

Elections of the workers delegates were, however, blocked by the socialists who

wanted to divert the workers from the elections to the armed struggle. On 5

March [O.S. 20 February] 1905, the Commission was dissolved

without having started work.

Following the assassination of his uncle, the Grand

Duke Sergei Aleksandrovich, on 17 February [O.S. 4

February] 1905, the Tsar agreed to give new concessions. On 18

February [O.S. 5 February] 1905, he published the Bulygin Rescript, which promised

the formation of a consultative assembly, religious tolerance, freedom of

speech (in the form of language rights for the Polish minority) and a reduction

in the peasants' redemption payments.

On 6 June [O.S. 24 May] 1905, Tsar had

received a Zemstvo deputation. Tsar confirmed his promise to convene an

assembly of people’s representatives.

The October Manifesto , written by Sergei

Witte and Alexis Obolenskii, was presented to the Tsar on 14 October

[O.S. 1 October]. It closely followed the demands of the Zemstvo

Congress in September, granting basic civil rights, allowing

the formation of political parties, extending the franchise towards universal

suffrage, and establishing the Duma as the central legislative body.

The Tsar waited and argued for three days, but finally signed the manifesto on

30 October [O.S.17 October] 1905, citing his desire to avoid a

massacre and his realisation that there was insufficient military force

available to pursue alternate options. He regretted signing the document,

saying that he felt "sick with shame at this betrayal of the

dynasty ... the betrayal was complete".

When the manifesto was proclaimed, there were

spontaneous demonstrations of support in all the major cities. The strikes in Saint

Petersburg and elsewhere officially ended or quickly collapsed. A

political amnesty was also offered. The concessions came hand-in-hand

with renewed, and brutal, action against the unrest. There was also a

backlash from the conservative elements of society, with right-wing attacks on

strikers, left-wingers, and Jews.

(October Manifesto: http://thoughtcrackers.blogspot.in/2015/10/the-russian-revolution-1905-revolution.html)

(October Manifesto: http://thoughtcrackers.blogspot.in/2015/10/the-russian-revolution-1905-revolution.html)

Results of 1905 Revolution:

During the 1905 Revolution, the Tsar allowed the

creation of an elected consultative Parliament or Duma. For a brief while

during the revolution, there existed a large number of trade unions and factory

committees made up of factory workers. After 1905, most committees and unions

worked unofficially, since they were declared illegal. Severe restrictions were

placed on political activity.

The October Manifesto served as a precursor to the

Constitution of 1906. It was reluctantly put into place by Tsar Nicholas II who

was convinced by Sergei Witte that it was necessary. Not

only was it necessary, but it is what finally stopped the 1905 Revolution and

kept Nicholas II in power for 12 more years. The opposition against the Tsar

government was far too strong to not have a manifesto written to attempt to

quell uprising. Witte was a strong proponent of a constitutional monarchy, an

elected parliament, and enumerated rights and freedoms within the constitution.

Creation of Duma and Stolypin:

The Duma's framework and power as controlled by the

government issued Fundamental Law (Constitution of 1906), which retained most

of the important functions of government to the Tsar.

The Duma proved to be an ineffective institution with the Tsar still always having an upper hand in control and power, and it could be dissolved and recalled by the Tsar at any time, both of which were often executed. Tsar dismissed the first Duma within 75 days and the re-elected second Duma within three months.

The Duma proved to be an ineffective institution with the Tsar still always having an upper hand in control and power, and it could be dissolved and recalled by the Tsar at any time, both of which were often executed. Tsar dismissed the first Duma within 75 days and the re-elected second Duma within three months.

In 1907, another manifesto was written by the tsar

to revise election law in the Duma, allowing for extreme manipulation by the

tsar to determine who was in the Duma. While the election framework of the Duma

is one that allowed for gerrymandering, the Duma was used as a platform for

those elected to have an opinion and have some ground in Russia’s bureaucracy

that the autocratic Tsar had to deal with.

The Third and Fourth Dumas also had very little to say for themselves, and the Duma existed until 1917 with the end of the Russian empire. Tsar did not want any questioning of his authority or any reduction in his power. He changed the voting laws and packed the third Duma with conservative politicians. Liberals and revolutionaries were kept out.

The Third and Fourth Dumas also had very little to say for themselves, and the Duma existed until 1917 with the end of the Russian empire. Tsar did not want any questioning of his authority or any reduction in his power. He changed the voting laws and packed the third Duma with conservative politicians. Liberals and revolutionaries were kept out.

Party

|

First Duma

|

Second Duma

|

Third Duma

|

Fourth Duma

|

Russian

Social Democratic Party

|

18 (Mensheviks)

|

47 (Mensheviks)

|

19 (Bolsheviks)

|

15 (Bolsheviks)

|

Socialist-Revolutionary

Party

|

–

|

37

|

–

|

–

|

Labour

group

|

136

|

104

|

13

|

10

|

Progressist

Party

|

27

|

28

|

28

|

41

|

Constitutional

Democratic Party(Kadets)

|

179

|

92

|

52

|

57

|

Non-Russian

National Groups

|

121

|

–

|

26

|

21

|

Centre

Party

|

–

|

–

|

–

|

33

|

Octobrist

Party

|

17

|

42

|

154

|

95

|

Nationalists

|

60

|

93

|

26

|

22

|

Rightists

|

8

|

10

|

147

|

154

|

TOTAL

|

566

|

453

|

465

|

448

|

Russian Constitution of 1906:

The Russian Constitution of 1906 was

published on the eve of the convocation of the First Duma. The new Fundamental

Law was enacted to institute promises of the October Manifesto as well as add

new reforms. The Tsar was confirmed as absolute leader, with complete control

of the executive, foreign policy, church, and the armed forces. The structure

of the Duma was changed, becoming a lower chamber below the Council of

Ministers, and was half-elected, half-appointed by the Tsar. Legislation had to

be approved by the Duma, the Council, and the Tsar to become law. The

introduction of the constitution states (and thus emphasizes) this:

- The Russian State is one and indivisible.

- The Grand Duchy of Finland, while comprising as inseparable

part of the Russian State, is governed in its internal affairs by special decrees

based on special legislation.

- The Russian language is the common language of the state, and its

use is compulsory in the army, in the navy and in all state and public

institutions. The use of local (regional) languages and dialects in state

and public institutions are determined by special legislation.

Through the Constitution’s introduction, it makes no

mention of any of the provisions of the October Manifesto. While it did enact

the provisions laid out previously, its sole purpose seems again to be to

propaganda for the monarchy and to simply not fall back on prior promises. The

Constitution lasted until the fall of the empire in 1917, and the provisions

coupled with the autocratic rule of the Tsar even under the new constitutional

monarchy were never enough for Russians and Lenin.

Rise of terrorism:

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)